To me, the most important lesson to draw from life of the

past is that no era is particularly more advanced than another. Sure, the

animals of one era may have features which were absent in the previous (i.e.

bones, eyes, etc.), but in general the most advanced periods of each era were

stocked with a diverse and unique array of life. What I’m trying to get at is

that, to me, it seems that the Cretaceous had just as many dinosaurs as the

Miocene had mammals. Different times, different environments, different groups

of animals, but neither one was better or more adapted to its surroundings than

the other.

|

| Gould's Wonderful Life focuses on the complexity of life in the Burgess Shale, pictured here. Painting by Carel Brest van Kempen. |

How can we make such an assumption? Surely their lack of

bones and complex eyes and lungs make them inferior to mammals, or reptiles, or

even fish. But success and diversity aren’t measures of body parts. They’re

measures of niches. The Cambrian was a hotbed of awesome creatures which filled

every niche available at the time. There were sponges, worms that preyed on

sponges, trilobites, arthropods that looked like trilobites, jellies, scaly

urchin-y things, “riddle teeth,” and giant predators measuring a whopping 1m in

length. Every niche, from benthic scavengers to macropredators was filled by

invertebrates of various phyla, some of which are now completely extinct.

If that wasn’t enough to convince you that the Cambrian

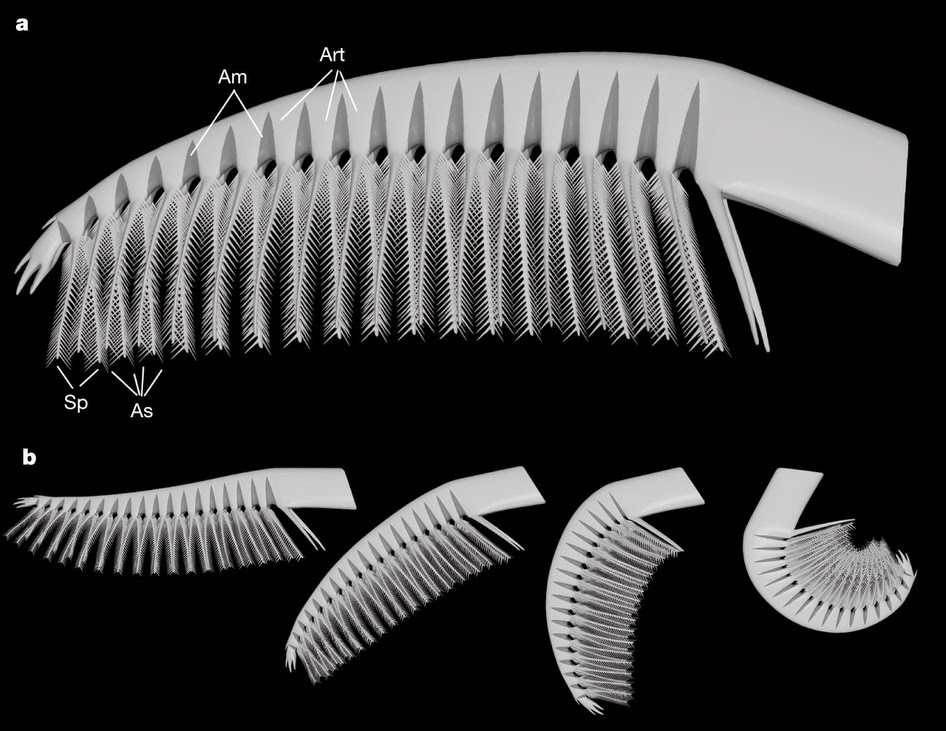

wasn’t an age of failed creatures, one recent discovery will. Tamisiocaris borealis is a newly-found

anomalocarid, a relative of the famous Cambrian critter Anomalocaris, one of the world’s first large predators. The

anomalocarids all feature “great appendages”* with adaptations which hint at a

predator lifestyle, with small spikes and barbs perfect for grasping prey and

articulating it into the ventrally-located mouth. What makes Tamisiocaris so special is that, instead

of having great appendages for grasping prey, it evolved long, feather-like

branches: Tamisiocaris was a

filter-feeder.

*Yes, this is the actual technical term.

That’s not such a stunning fact now: in the hundreds of millions of years since the Cambrian,

filter-feeding has independently evolved across the animal kingdom, from whales

to pterosaurs. But in the Cambrian, there was nothing that lived even a

remotely close lifestyle. Tamisiocaris

was the first creature we know of that evolved from its carnivorous, predatory

ancestors to a lifestyle of peaceful planktivory. Instead of noshing on crunchy

trilobites near the sea floor, it could glide along in the open ocean, using

its huge brush-like great appendages to trap primitive plankton and other tasty

vittles.

To me, this is the most exciting fossil found in recent

years. Sure, reptiles will always have a special place in my heart, but when we

find fossils from the Cambrian, especially ones which totally shake our idea of

what it means to be ancient, and not primitive, we view our earth in a much

more realistic, and much less mammalian-biased, light.

|

| Reconstruction of Tamisiocaris and other Cambrian critters by Rob Nicholls. |

No comments:

Post a Comment